Spending Time With Dead Folks May Be The Best Thing You Do Outside in October

There's a serious case for spending time in cemeteries while you're still above ground.

In writing Outdoor Humans, my goal is to encourage you to spend more time in nature. However, I fully acknowledge not everyone has access to the grandeur of greenspaces or even a backyard. Stepping into quiet, natural areas isn’t possible from every neighborhood — an estimated one-third of Americans can’t even get to a park within 10 minutes of walking. However, there’s one natural area that exists in nearly every community that I’d highly recommend visiting: a cemetery.

Many people shiver at the idea of spending any more time than necessary in a cemetery, and the idea of willingly hanging out there may sound bewildering. But there’s a strong argument for it — and a history of it.

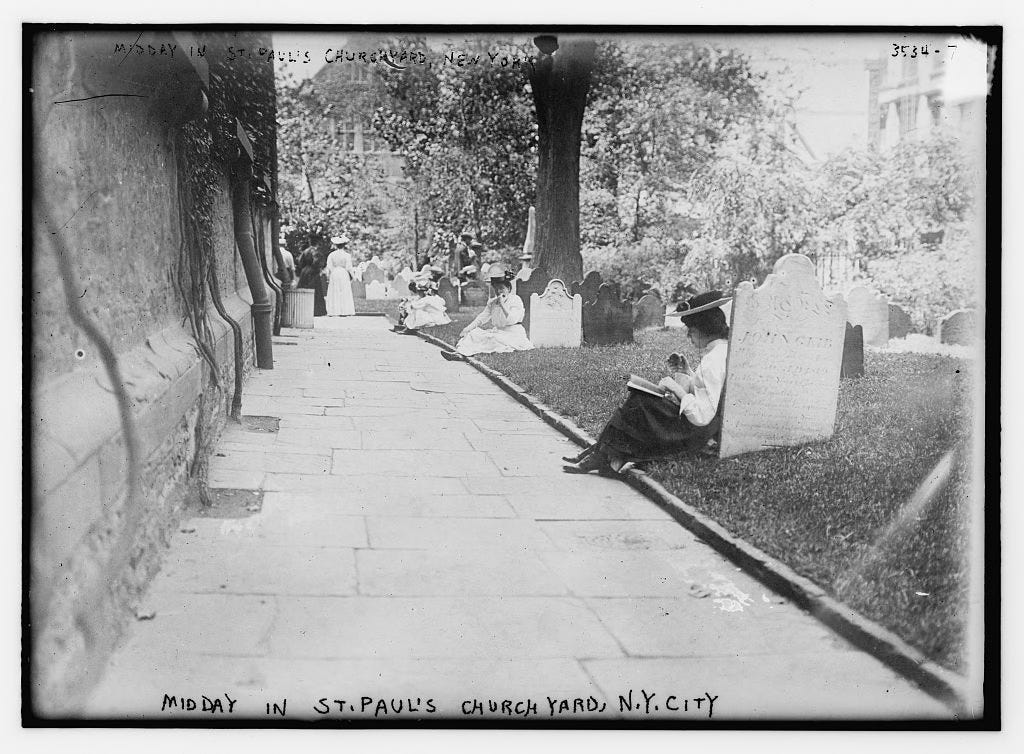

Before public parks were widespread features of the American landscape, there were cemeteries. Beautifully manicured and designed like outdoor art museums full of memorial sculptures, these spaces weren’t exclusively for the dead. Around the 1830s, cemeteries slowly transformed from crowded churchyard plots to expansive landscapes, with the belief they’d provide rest for the deceased and the living. Urban planners viewed them as gardens where the dead peacefully slumbered and the living could walk winding paths packed with plants and symbolism, refreshing their senses dulled by busy city life.

With limited access to nature, Victorian-era society flocked to these memorial parks, picnicking among the headstones of loved ones long gone. Very demure, very mindful… except not. Cemeteries were spots for promenading with friends, hunting and shooting, and even carriage racing. Some burial grounds became such 19th-century hotspots that groundskeepers established strict rules banning food altogether or required admission tickets (no getting in without knowing a member of the interred).

By today’s standards, those activities would be downright disrespectful, but that could be a bit of modern day projection.

“We’re probably more narrow-minded about what is and isn’t appropriate in a cemetery now than we ever have been before,” says Bess Lovejoy, cemetery sage and author of Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses. While Bess isn’t advocating for you to hold a boisterous party among the mausoleums, she does believe these spaces are meant to be enjoyed while we’re still alive. “There’s an argument that it’s kind of a beautiful co-mingling of death and life,” she says. “It’s always death and life together.”

Cemetery picnicking slowly fell out of favor around the 1920s for a multitude of reasons. As the Victorian era faded, so did the romanticized approach to death and mourning. Mass deaths during the 1918 influenza pandemic and following world war disrupted how people expressed grief. The rise of funeral home services helped Americans disconnect from regularly interacting with reminders of mortality.

Just because society stopped enjoying nature in cemeteries doesn’t mean we can’t return to doing so. Adapting forest bathing to a different location — perhaps call it “cemetery bathing” — can provide scientifically backed perks for our brains and bodies, which is in part why Bess recommends it.

“To me, it combines both the nature and history side of things,” she says. “You’re lowering your stress levels. You’re breathing in all kinds of good organic compounds. You’re looking at green, which is calming and soothing to our little human brains. But you’re also communing with history.”

Like other forms of meditation, “cemetery bathing” may help us center ourselves in the bigger picture of life. “I think having some connection to mortality isn’t totally a bad thing for us,” Bess says. “It helps us focus on what matters, to some extent. For me, the sense that things are going to end can kind of sharpen things and put them into focus.”

And in a world that feels increasingly complex, out-of-control, and divisive, cemeteries may instill a sense of humanity. “It deepens our appreciation for each other to know that we’re all a limited-time offer,” Bess says.

I couldn’t agree more.

5 Tips for Enjoying Your Time Among the Dead

If the idea of spending an hour relaxing in a cemetery intrigues you, Bess offers up a few tips for getting started. Venture out for an hour or an afternoon — however long gives you the chance to rest your very alive bones.

1. Keep an eye out for cemetery happenings. Bess recommends observing your surroundings and following any posted burial ground rules. “Be aware of active funerals going on around you, or mourners,” she says. “Not that you necessarily need to do anything different, but it’s good to be aware of what’s going on.”

2. Slow down and enjoy what you’re seeing. “There can be beautiful little tableaus that happen. Falling leaves or cherry blossoms collecting on a grave, or acorns nearby,” Bess says. “Look for the squirrels or the chipmunks or the lizards, depending on where you are in the world, because you’ll often find cemeteries can be little nature refuges depending on how they’re maintained.” She adds it’s not uncommon to see wildlife in these quiet spaces who, just like you, are seeking sanctuary from the busier parts of cities.

3. Be curious. “If you have questions about who you’re looking at, pull up Find A Grave [a digital cemetery database], and often it will tell you some information,” Bess says. You may come across an interesting life story — she once stumbled across an intriguing headstone that wound up belonging to a murderer. Many graves have a sweeter side, like headstones that share beloved family recipes.

4. Consider your impact. Bess cautions against the controversial practice of making headstone rubbings. Doing so risks damage to delicate, aging markers (take a photo instead). On some occasions, you may feel compelled to leave a memorial. “Ideally, don’t leave anything. If you feel moved to leave flowers, that might be OK, but ideally natural flowers, not plastic,” Bess says. Many historians also advise against removing anything from a grave. Stones, shells, and other artifacts set atop often have cultural meaning and should be left alone.

5. Shake the spooky feeling. Death is inherently frightening. We can’t stop it and tend to view dead things with fear, but it doesn’t have to be that way. “I hope that people can get beyond the idea that just because [someone is] dead, they’re spooky and cursed in some way,” Bess says. “We all have ancestors. We’re all going to become skeletons someday. Death is a part of the human experience.”

If you’re looking for burial grounds to spend your time in, Bess recommends checking out 222 Cemeteries to See Before You Die by author and cemetery expert Loren Rhoads. And might I suggest adding Bess’ books — Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses and Northwest Know-How: Haunts — to your reading list? They’re both perfect autumnal reads that may inspire your next cemetery stroll.