May 2024: Hello From the Outdoors

Spring is in full swing. Grab your allergy meds and get outside. (After reading this, of course!)

In this month’s issue:

Tips on finding morel mushrooms (there’s still time!)

How to easily identify wildflower blooms, like the ones you come across on this month’s recommended walk/hike

The care and keeping of hummingbirds

Brace yourself: trillions of cicadas are coming, and there’s nothing you can do about it (except buy earplugs)

Plus a few other nature notes.

Hello, friends!

Welcome to the first issue of Outdoor Humans, a monthly newsletter that hopefully inspires you to spend a little more time in nature. Wow! I started a thing, but also hate endless small talk about starting a thing, so let’s dive in.

May is perhaps my best month of the year. I mark the end of another monotonous Midwestern winter, shove my trusty SAD lamp back into the closet, and head out to my garden for some one-on-one time with serotonin-boosting soil microbes. I feel like a better person than I was during the gray months of the year, no longer pulled between two worlds: the “human” version saddled with nonstop work deadlines and tasks, and nature’s cyclical pattern of growth and rest encourages winter hibernation. It’s hard to juggle both, and I tend to feel out of sync with nature until spring returns.

While we might forget that we’re guided in part by nature’s calendar, our bodies don’t. Research from Stanford Medicine shows that more than 1,000 molecules inside our ol’ bone bags react to two seasonal shifts: late spring to early summer, and late fall to early winter. At these points in the year, our bodies trigger tons of small mechanisms of which we are generally oblivious. Some are helpful, like how the PER1 gene is most active in spring, helping to regulate our sleep-wake cycles; others are annoying yet understandable, like the rise in inflammatory biomarkers that fuel our seasonal allergies.

Recognizing that we’re just as much a part of nature despite our best attempts otherwise isn’t just a fun fact — it may be crucial to our future. A 2023 report from the European Environment Agency found that humans impact Earth more than any other species, yet we don’t often acknowledge how deeply we are interconnected with our ecosystems. We can’t fully protect the most vulnerable parts of our planet without developing this understanding.

You don’t have to be a biologist to gain that awareness. Instead, I hope you’ll take just a few moments of mindfulness this month to re-sync your system. My favorite way is sitting outside for five to 15 minutes each morning with a cup of tea. It gives me a chance to listen to birds, feel the wind, and just relax. Sometimes I read, or paint my toenails, but I always leave my phone inside.

The human world can wait just a few more minutes.

This month, outdoors

A few ideas of how you can enjoy what nature has scheduled for May

🍄 A 5-Minute Guide To Finding Your Own Morels

Mushroom hunters are a particularly secretive group. I’ve been lucky enough to find a good mess of morel mushrooms in my own secret spots this spring, and while I’ll gladly share that I did find them, I am entirely unwilling to share where I harvested them (even my 6-year-old, who enjoyed his first mushrooming successes this year, has been sworn to secrecy). It might be gatekeeping, though I have good reason: morels are tricky to find, growing low to the ground and blending with leaves and downed limbs. Morchella mycelium is also particularly finicky, so much so that researchers and farmers have found it difficult to cultivate these shrooms on a large scale. Wild areas that previously produced bumper crops of mushrooms can unexpectedly dry up due to environmental changes, major ground disturbances, or just because. For these reasons, mushroom hunters who sell their harvests can bring in big bucks — the lowest going price around St. Louis this year was $60 per pound — creating even more of an incentive to not squeal about your spot.

I’ve hunted for morels off-and-on since I was a teenager, but by no means am I a mushrooming expert. Frankly, I don’t think you have to be, either. You do, however, have to know the bounds of your knowledge when foraging wild foods. This season, I relied on a pocket guide from the Missouri Department of Conservation (free to download) as a refresher, which shows the three variations you may come across. While I only found common morels (Morchella americana), my hawk-eyed mom was able to add black morels (Morchella angusticeps) and half-free morels (Morchella punctipes) to her basket. All are deliciously edible, and there’s still time for you to find them, too.

When to hunt: Early April through mid-May

Morel season is incredibly weather dependent, starting when daytime temperatures reach into the 70s and evenings hit around 50 degrees, allowing soil temps to rise. You don’t have to track the weather meticulously; I follow the old timely lore that morels appear at the same time mayapples (Podophyllum peltatum) spring up. Precipitation is also important — morels like moist but not boggy conditions, so a too-dry or overly wet spring isn’t favorable to finding many.

Where to look: Anywhere that’s not too wet or too dry

There’s no specific environment that morels stick to (remember, I said they’re tricky!) though you may have luck alongside creeks and waterways that are moist, but not soggy. According to MDC, it’s worth checking out areas that have recently experienced flooding or wildfires, since those spots can spring up morels. Hunting around some trees may also increase your odds: elm, ash, and cottonwood trees seem to support morel growth.

Up next: Safely identifying mushrooms

If you’ve been lucky enough to find a few morels, now’s the time to double-check that you’ve gotten the right thing. Is the coloring correct? Is the mushroom entirely hollow inside when cut in half? Does the mushroom cap have ridges and pits (versus folds or lobes)? It’s time to pull up your trusty reference guide and compare what you’ve found — false morels do exist, and while some people do eat them, mycologists do not recommend doing so. I love mushroom hunting with a more experienced forager who knows what they’re looking for, but that’s not always possible — here’s where living in modern times helps. Mushroomers have converged in countless Facebook and Reddit groups to confirm their finds, share expertise, and of course, brag a fair bit.

Note: If you’re ever unsure about a mushroom, toss it. Take your joy from the hunt and a bit of time spent outdoors, and try again. Getting sick is never worth it.

How to eat them: Fried, sautéed, or in a cream sauce.

The decision is yours alone — I personally love them lightly battered and fried, but it’s up to your taste buds. The hardest part of morel hunting may be pacing yourself at the dinner table. 🍄

🪺 The Care and Keeping of Hummingbirds

Welcome back, hummingbirds! I was lucky enough to spot my first ruby-throated hummers this week and promptly put out my nectar feeders, though I can’t tell if I have two new Best Bird Friends™ or it’s just the same bird fueling up over and over again. Attracting hummingbirds is relatively easy, and enjoyable — they’re mischievous and territorial little flyers who will pull amazing acrobatic stunts to compete for a sip of that good, good sugar water. Here’s a few ways you can best serve the hummingbirds that visit your home should you decide to attract a few.

Do: Purchase a hummingbird feeder that’s easy to clean

Unlike seed feeders for songbirds, hummingbird feeders need regular cleaning to keep bacteria growth at bay. When left too long in the heat, sugar nectar can grow some pretty gnarly slime and grime. Feeders should be rinsed with warm water once or twice a week — this often syncs with how often the birds need a refill. You’ll find tons of plastic feeders out there on the cheap, but I recommend finding a glass option. They’re sturdier, clean easily, and last longer. (Pro tip: I buy new feeders on clearance at the end of summer to save a few bucks.)

Do: Make your own hummingbird nectar mix

There’s nothing special about hummingbird food from big box stores. You can make your own at home by simply dissolving 1/4 cup of white granulated sugar in 1 cup of hot water. (The magic ratio is 1:4, so expand your batch as needed using this formula.) Let it cool before adding to your feeder, and store any extra in the fridge for use later in the week.

Don’t: Add food dye to your hummingbird nectar

Some commercial nectars use red dyes to help attract hummingbirds, though it’s not necessary (all that red dye 40 may actually be harmful). The Audubon Society recommends steering clear of store-bought nectars that use red food dyes. Skip the red food coloring at home, too.

Don’t: Fret if you’re not instantly seeing hummingbirds

They may not be in your area yet. Hummingbirds slowly spread throughout the country between late March and early May, with males arriving first and females a week or two later. You can also encourage them to pit stop at your feeder by making the surrounding area more attractive with eye-catching red flowering plants (bonus points for selecting native species that cater to multiple creatures in your environment). With a lifespan of 3 to 5 years, hummingbirds often return season after season to spots where they last found food, so if you had successful feeders up last year, you’ll want to put them back in the same location.

Don’t: Panic about avian flu

H5N1 is a big deal in the news right now, and I got to wondering if it’s transmissible to hummingbirds. It appears that hummingbirds have a reduced risk of catching avian flu based on their feeding and behavior habits, though there’s not much research on them specifically. Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology updated its guidelines Tuesday on feeding wild birds during avian flu outbreaks. Although hummingbirds weren’t mentioned by name, Cornell advises that wild songbirds and “typical feeder visitors” tend to have a low risk of catching the illness, and account for less than 2% of all wild bird flu cases. It’s OK to continue feeding wild birds (just remember to clean those feeders and birdbaths on the reg).

Do: Make some new friends

Research shows that hummingbirds have incredibly sharp memories, and may be capable of remembering human faces. So if you end up bonding with these tiny flying baddies, there’s a good chance you could see them again and again, and even next year. 🪺

🌼 A Few Resources to Help With Wildflower ID

April has come and gone, hopefully taking with it the deluge of spring storms that have ripped across the country. That means it’s time to enjoy the perks of all that rain: wildflower season is kicking off. The first full week of May (5-11) marks National Wildflower Week, perfectly timed to celebrate many emerging blooms. While wildflower blooms won’t peak until mid-summer or later, it’s still enjoyable to get out and see what’s blooming now with a walk, hike, or leisurely stroll through the neighborhood.

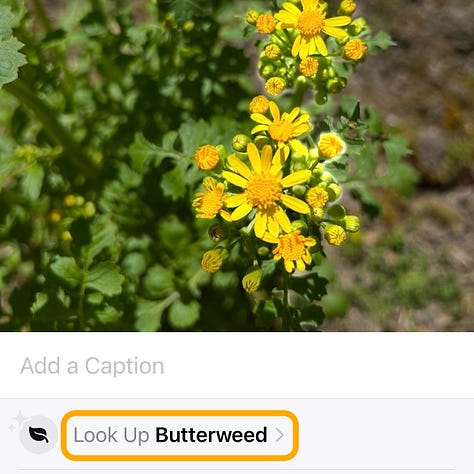

While on that wildflower wander, you may wonder, “What am I looking at here?” I have two tips for finding out just that, because I’m a sucker for snapping a photo of nearly every flower I come across for identification. Here’s how I use the merits of AI to learn wildflower species, and how you can, too.

Using Visual Lookup (for iPhones)

I stumbled upon this little iPhone hack by accident, and most of the time it works. After photographing your flower, open the Photos app and pull up the photo you just took. At the bottom, you’ll see the info symbol — clicking this triggers your phone to use Visual Look Up to identify the flower in question. Most of the time, this generates an accurate response nearly instantly; other times, you may just see “Look Up Plant.” Photo quality plays a big role here, and it may be beneficial to take photos from different angles to help. You can browse results to verify Visual Look Up has the right plant, and click through for more info. This trick also works for butterflies, birds, non-flowering plants, and other natural features.

Using the Seek app by iNaturalist

I’ve recently downloaded the Seek app, which uses your phone’s camera to identify plants, trees, fungi, and wildlife. You can watch the app work through the thinking process as it generates an answer; it then captures a photo and pulls up information about whatever you’ve found. Seek also stores your observations for later review, and in an effort to get you exploring outdoors, offers monthly challenges that reward you with badges. In May’s “Phenology Challenge,” finding 10 examples of flowering, fruiting, or animal migrations will earn you a badge and some quality outdoor time. 🌼

🐝 A Very Bridgerton Crossover

I know that some of my dear readers are counting down the days until Shondaland and Netflix finally grace us with season three of Bridgerton. New episodes drop in two agonizingly long weeks, but in the meantime you may find it of interest to promenade in search of the very creatures that represent the Bridgerton family: bees! Honey bee colonies often hunt for a new home this time of year — colonies typically split in late spring to early summer as new queens are born and old queens depart with a small portion of the colony to set up a new hive.

I had a chance to watch a wild swarm last spring and found it entrancing; I was initially alerted by a loud, consistent buzzing and increased bee activity around my home. Following both clues (a trick called “bee lining”), I was able to eventually spot a swarm about 50 feet up a tree. Watching bee swarms is generally safe, considering bees in search of new real estate are typically less aggressive without a hive to defend, though they should still be viewed at a distance to avoid disturbing their busywork. Still, if you are allergic to our pollinating friends, please take particular care when bee watching. We wouldn’t want any members of the ton to face the same anaphylactic fate as the beloved Edmund Bridgerton. [Bonus points if you read this segment in Lady Whistledown’s voice, narrated by the great Julie Andrews.]

May 20 marks World Bee Day — the perfect opportunity for this activity.

Arrivals, departures, and other nature notes

May 4 marks National Weather Observers Day. If, like me, you have the hallmark Midwestern instinct to stare at severe weather instead of taking shelter (why are we like this?), you may find the National Weather Service’s citizen scientist programs to be of interest. I attended a SKYWARN Storm Spotter training a few years back; the class lasted about two hours and I walked away with a better understanding of how storms develop, markers of severe weather, and how to accurately report what you see to help meteorologists collect data.

A bunch of awfully loud bugs are about to show up. Yup, I’m talking about cicadas. Trillions of cicadas are close to emerging from the ground, generally once soil temperatures hit 64 degrees. This year marks a rare “dual emergence” where two major broods — XIII and XIX — will make their synced appearance. This timing happens every 221 years, the last being 1803 when Thomas Jefferson was president. Cicadas are commonly confused with locusts, though they’re not even related species (locusts look more like grasshoppers, while cicadas… well, they’ve got a face only an entomologist could love). Unlike locusts, cicadas won’t decimate your plants or trees. While they may sip on water or tree sap, they’ll be primarily focused on doing one thing with their limited time above ground: mating. After they’ve accomplished that feat, they’ll lay eggs, die, and litter your lawn until nature does its cleanup work.

While I find cicadas’ 13 to 17-year lifespan a marvel, they’re far from my favorite insect. As a kid, my mom once stuck their shells to her shirt and pretended she was being eaten as a prank. During 2011’s emergence, I was working as a news intern and had to stand under a tree of screeching cicadas that continuously landed in my hair while being on TV. In both cases, I was emotionally traumatized but entirely safe — cicadas do not bite since their mouths consist of straw-like proboscis, just like butterflies.

Some snakes have high hopes for finding a mate this time of year. A variety of species across North America are in the streets (figuratively and literally) as summer approaches. Some, like black rat snakes and northern water snakes, shake it up by mating in trees. Others, like garter snakes, can form “mating balls,” where a female snake is essentially mobbed by and entangled in a group of suitors fighting to mate. Give these ahem… determined creatures some space and credit — even if snakes give you the creepy crawlies, they’re crucial members of our ecosystems tasked with keeping rodent populations in check and even dispersing seeds.

“Shellebrate” World Turtle Day on May 23, timed appropriately for turtle nesting season in North America. Watch out for turtles crossing busy roadways, and if you stop to help, be sure you’re moving them in the direction they’re going and in a way that prevents injury. Picking up turtles by their tails is a big nope, and lifting by their top shell alone can cause injury since their spines and shells are a fused unit. Experts recommend picking up box turtles with both hands, placing your thumbs on the top shell and fingertips under the plastron (aka bottom shell) to provide maximum support. Check out this video for a clear visual. If you’re nervous about getting accidentally scratched, just reach for a good pair of work gloves.

Nature in the news

A few recommendations of things I’ve read, watched, or listened to this month

[Podcast] “The Evolving Danger of the New Bird Flu” from The Daily

Much of the discussion about the H5N1 avian flu is centered on its spread to dairy cows in the U.S., but The Daily’s team explains how the virus is also spreading into penguin colonies and decimating sea mammal species, including elephant seals and sea lions.

[Article] “Move Over, Cicadas: These Living Things ‘Go Dark’ For a Long Time, Too” from Smithsonian Magazine

This summer’s buzz about the cicada invasion from hell has spun off a lot of content, but I really enjoyed this piece about other underground-dwelling creatures, too. Even plants get in on exceptionally long dormancies — like so called “Rip Van Winkle” orchids that stay underground for up to 20 years before sprouting.

[Article] “A Mix-Up Over Bioengineered Tomato Seeds Sparked Fears About Spread of GMO Crops” from NPR

If you dabble in the gardening world (as one does), you’ve likely heard of Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds, a Missouri-based seed supplier that has cultivated a mass following thanks to 20-plus years of supplying non-GMO seeds. Baker Creek’s highly touted tomato species of 2024 — “Purple Galaxy” — has turned out to be the antithesis of the company’s branding, and questions have arisen about how this bio-engineered seed even landed on the company’s shelves.

Shameless plugs for my work around the web

I’ve been doing a bit of garden-related writing for Better Report as of late. Here are a few pieces from my “not-spent-outside” day job that you may find helpful this spring.

That’s it for this month’s edition of Outside Humans. We’ll chat again in June.

I want to thank everyone who has subscribed, shared, and chatted with me about the newsletter thus far. It’s truly wonderful to have a chance to write about the things I find fascinating, made all the better by sharing with people who enjoy them, too.

Thanks for reading, but more importantly: go get outside!

Nicole Garner Meeker

Great first edition! Well written and informative.