October 2024: Spooky Scary Edition

You can’t find scary things in the woods if you’re not out there.

In this month’s issue:

Author Bess Lovejoy explains why you should be spending more time in cemeteries while you’re still above ground

Make like a squirrel and start hoarding walnuts as they ripen this month

The creepiest mushrooms are making an appearance

Your reader questions answered: “Will this spider kill me?”

Plus a few other nature notes.

Hello, friends!

Seventy-seven Octobers. If I live the average life of the average American, I can hope to experience the crisp, petrichor-scented days of October 77 times. It simultaneously feels like a gratuitous and insufficient amount of time.

This time of year brings to light our delicate existence in the world. Pumpkin patches and spiced lattes aside, autumn delivers an immersive reminder that we exist in the natural cycle of birth, growth, and death. After a busy summer of play ends, we begin to slow down, spend more time snuggled up on the couch, and maybe get a little tinge of existentialism when Death Cab for Cutie pops on our playlists. As the natural world slowly marches toward a winter of rest, so do we. What an uplifting start to this month’s issue, right?

And yet, with all these very in-your-face reminders of impermanence, we find joy in spite of it. We morbidly joke about death around Halloween, light candles as the daylight hours slip away, and savor the crunch of dead leaves underfoot. Fall becomes one of the most beautiful times of year so many of us anticipate, especially when it comes to getting outside: fewer sunburns, hiking further without sweating, and peaceful mornings with breathtaking views.

The more I think about it, 77 Octobers feels like too little time to revel in this magnificent season. But with only 43 left to go, I better get out there… and maybe you should, too.

This month, outdoors

A few ideas of how you can enjoy what nature has scheduled for September

🪦 Spending Time Outside With Dead Folks May Be The Best Thing You Do This Month

In writing Outdoor Humans, my goal is to encourage you to spend more time in nature. However, I fully acknowledge not everyone has access to the grandeur of greenspaces or even a backyard. Stepping into quiet, natural areas isn’t possible from every neighborhood — an estimated one-third of Americans can’t even get to a park within 10 minutes of walking. However, there’s one natural area that exists in nearly every community that I’d highly recommend visiting: a cemetery.

Many people shiver at the idea of spending any more time than necessary in a cemetery, and the idea of willingly hanging out there may sound bewildering. But there’s a strong argument for it — and a history of it.

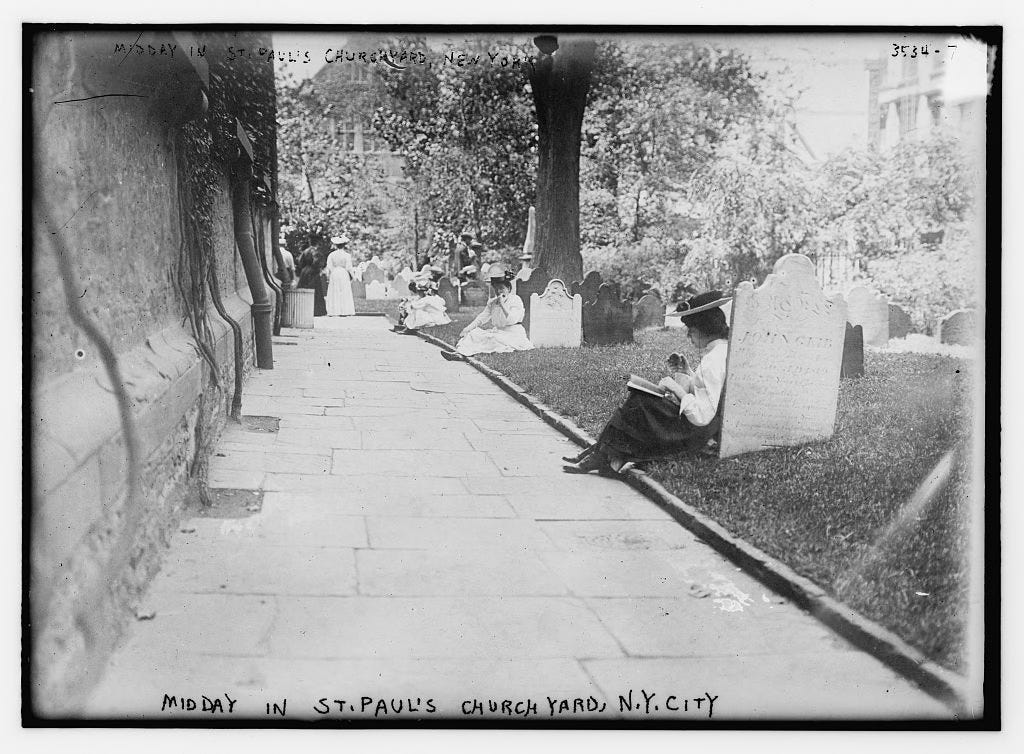

Before public parks were widespread features of the American landscape, there were cemeteries. Beautifully manicured and designed like outdoor art museums full of memorial sculptures, these spaces weren’t exclusively for the dead. Around the 1830s, cemeteries slowly transformed from crowded churchyard plots to expansive landscapes, with the belief they’d provide rest for the deceased and the living. Urban planners viewed them as gardens where the dead peacefully slumbered and the living could walk winding paths packed with plants and symbolism, refreshing their senses dulled by busy city life.

With limited access to nature, Victorian-era society flocked to these memorial parks, picnicking among the headstones of loved ones long gone. Very demure, very mindful… except not. Cemeteries were spots for promenading with friends, hunting and shooting, and even carriage racing. Some burial grounds became such 19th-century hotspots that groundskeepers established strict rules banning food altogether or required admission tickets (no getting in without knowing a member of the interred).

By today’s standards, those activities would be downright disrespectful, but that could be a bit of modern day projection.

“We’re probably more narrow-minded about what is and isn’t appropriate in a cemetery now than we ever have been before,” says Bess Lovejoy, cemetery savant and author of Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses. While Bess isn’t advocating for you to hold a boisterous party among the mausoleums, she does believe these spaces are meant to be enjoyed while we’re still alive. “There’s an argument that it’s kind of a beautiful co-mingling of death and life,” she says. “It’s always death and life together.”

Cemetery picnicking slowly fell out of favor around the 1920s for a multitude of reasons. As the Victorian era faded, so did the romanticized approach to death and mourning. Mass deaths during the 1918 influenza pandemic and following world war disrupted how people expressed grief. The rise of funeral home services helped Americans disconnect from regularly interacting with reminders of mortality.

Just because society stopped enjoying nature in cemeteries doesn’t mean we can’t return to doing so. Adapting forest bathing to a different location — perhaps call it “cemetery bathing” — can provide scientifically backed perks for our brains and bodies, which is in part why Bess recommends it.

“To me, it combines both the nature and history side of things,” she says. “You’re lowering your stress levels. You’re breathing in all kinds of good organic compounds. You’re looking at green, which is calming and soothing to our little human brains. But you’re also communing with history.”

Like other forms of meditation, “cemetery bathing” may help us center ourselves in the bigger picture of life. “I think having some connection to mortality isn’t totally a bad thing for us,” Bess says. “It helps us focus on what matters, to some extent. For me, the sense that things are going to end can kind of sharpen things and put them into focus.”

And in a world that feels increasingly complex, out-of-control, and divisive, cemeteries may instill a sense of humanity. “It deepens our appreciation for each other to know that we’re all a limited-time offer,” Bess says.

I couldn’t agree more.

5 Tips for Enjoying Your Time Among the Dead

If the idea of spending an hour relaxing in a cemetery intrigues you, Bess offers up a few tips for getting started. Venture out for an hour or an afternoon — however long gives you the chance to rest your very alive bones.

1. Keep an eye out for cemetery happenings. Bess recommends observing your surroundings and following any posted burial ground rules. “Be aware of active funerals going on around you, or mourners,” she says. “Not that you necessarily need to do anything different, but it’s good to be aware of what’s going on.”

2. Slow down and enjoy what you’re seeing. “There can be beautiful little tableaus that happen. Falling leaves or cherry blossoms collecting on a grave, or acorns nearby,” Bess says. “Look for the squirrels or the chipmunks or the lizards, depending on where you are in the world, because you’ll often find cemeteries can be little nature refuges depending on how they’re maintained.” She adds it’s not uncommon to see wildlife in these quiet spaces who, just like you, are seeking sanctuary from the busier parts of cities.

3. Be curious. “If you have questions about who you’re looking at, pull up Find A Grave [a digital cemetery database], and often it will tell you some information,” Bess says. You may come across an interesting life story — she once stumbled across an intriguing headstone that wound up belonging to a murderer. Many graves have a sweeter side, like headstones that share beloved family recipes.

4. Consider your impact. Bess cautions against the controversial practice of making headstone rubbings. Doing so risks damage to delicate, aging markers (take a photo instead). On some occasions, you may feel compelled to leave a memorial. “Ideally, don’t leave anything. If you feel moved to leave flowers, that might be OK, but ideally natural flowers, not plastic,” Bess says. Many historians also advise against removing anything from a grave. Stones, shells, and other artifacts set atop often have cultural meaning and should be left alone.

5. Shake the spooky feeling. Death is inherently frightening. We can’t stop it and tend to view dead things with fear, but it doesn’t have to be that way. “I hope that people can get beyond the idea that just because [someone is] dead, they’re spooky and cursed in some way,” Bess says. “We all have ancestors. We’re all going to become skeletons someday. Death is a part of the human experience.”

If you’re looking for burial grounds to spend your time in, Bess recommends checking out 222 Cemeteries to See Before You Die by author and cemetery expert Loren Rhoads. And might I suggest adding Bess’ books — Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses and Northwest Know-How: Haunts — to your reading list? They’re both perfect autumnal reads that may inspire your next cemetery stroll.

🌰 A-Tisket, A-Tasket, Walnuts In Your Basket

Fruit trees have had their spotlight this year, and with summer departure, it’s the nut-producing trees that shine brightest this time of year. Grab your foraging basket — or rather several buckets — because walnuts are both in-season and plentiful.

When to hunt: Autumn through early winter

Black walnut trees (Juglans nigra) can start dropping their season’s harvest as early as mid-September in some regions; for me here in Missouri, I tend to find them littering my driveway around mid-October. The hulls don’t fall all at once, but over the course of several weeks, and the season can continue through December.

How to harvest: The trees willingly giveth

Walnuts are easy to harvest because the trees tend to do most of the work. As they ripen, the hulls detach from the tree, and you’ll find them easily collectible below. You can shake smaller trees to drop more nuts, but lookout below, because these hefty pods can do some damage. The hulls — aka the exterior shell that protects the actual walnut — have a gritty texture and start off with a lime-green hue, transitioning to a nearly black shade the older they get. I find that walnuts harvested earlier in the season while the hulls are still green have better flavor than nuts collected later in the year.

Foraging notes you should know

I’m warning you: be careful what you wear when working with walnuts. These forageable foods produce a substance called juglone within its husk that can stain hands and clothing (some people even find it irritating or blistering to their skin). Skin staining can take days or weeks to disappear, and I have had clothing permanently discolored. However, if you partake in the fiber arts (hello fellow knitters, weavers, and fabric hoarders!), you can repurpose this ink to make your own natural dye.

Walnuts are also notoriously difficult to crack. Some foragers dump their finds in the driveway and roll over the hulls with their cars; other people use a hammer (my children find this exciting, but it is messy and wild). Despite the tough work, removing the walnuts from their exterior shell is essential for actually eating them. Once they’re broken free, the nuts need a little storage time before they’re ready to eat; some experts recommend letting them air-dry for about a month. Which means if you get started now, there’s a good chance you’ll be able to add fresh walnuts to your Thanksgiving or winter holiday baking.

Arrivals, departures, and other nature notes

What to look for on this month’s outdoor adventures

There’s a tiny moon rising. Believe it or not, Earth will technically have two moons this harvest season. In August, astronomers began watching asteroid 2024 PT5, a space rock that would likely be pulled into Earth’s orbit in late September. This mini moon is estimated to hang around until Nov. 25, though don’t expect to catch a glimpse of it. At just 24-feet wide, the asteroid pales in comparison to the actual moon (which measures about 2,159 miles wide). You won’t be able to see the mini moon with the naked eye or even a telescope, but knowing it’s there is a fun trivia tidbit.

These mushrooms might just reach out and grab you. Just kidding, though Dead Man’s Fingers (Xylaria polymorpha) may give you a good scare. These aptly named fungi grow along rotting tree stumps, protruding from the base like charcoal-colored fingers and reaching up to 3 inches in height. The zombie-looking growths expand year-round and become more scraggly and elongated as fall carries on. They’re not edible but are fun (and a little eerie) to spot.

Alfred Hitchcock could have made a Birds sequel with these pests. Brown marmorated stink bugs often creep along warm window ledges and building exteriors in swarms that can make your skin crawl. And even worse: they’re looking to spend the next few months indoors with you. Halyomorpha halys are invasive pests first discovered in Pennsylvania in 1998 and have spread along the coasts and toward the Midwest in the decades since. Without any native predators, stink bug populations have thrived, becoming a true nuisance — they attack gardens and vegetable crops by piercing plants to feed on their juices, and the bugs produce a rancid smell when squished that can trigger allergies or skin irritation. Home pesticide treatments are generally ineffective against them, but you do have one helpful tool at your disposal à la Ghostbusters: your vacuum.

Collect these seeds. I promise they won’t sprout an Audrey II. Milkweed (Asclepias spp.) seeds are literally popping off this time of year, and collecting just a few can help spread this beneficial species throughout your yard. Milkweed pods resemble bumpy, elongated horns that transform from light green to beige or light gray as they prepare to burst. They’re ready to collect when the pods pop open with a soft squeeze and reveal rich brown seeds within. Be sure to take just a few pods if you find them, leaving enough for nature to sow next year, and keep the ones you amass in a cool, dry spot until they’re ready to plant in spring.

Ask the Woods Witch: Your Nature Questions, Answered 🔮

This month’s question comes from Mallory F. in Ballwin, Missouri:

Look at this monster outside my front porch. Is it venomous?

Mallory has been graced with the presence of an absolute queen — a yellow garden spider (Argiope aurantia). This gorgeous gal is a large, orb-weaving spider, meaning she spins a complex circular web, possible because of an additional claw at the end of each leg. Those webs often contain thick zig-zags called stabilimentum. Scientists aren’t sure why spiders add this feature but believe it could catch birds’ attention and keep them from flying through webs.

Like many spider species, female A. aurantia are larger than their male counterparts, stretching 1.1 inches in body length, which does not include those eight legs. Yellow garden spiders are found throughout North America and are harmless to humans; while they produce venom that can immobilize wasps, bees, and other bugs, they typically flee in the presence of humans. Catch a glimpse of them in sunny spots before frost arrives — cool weather marks the end of their lifecycle.

Have a nature question? Submit your outdoor query and receive a thoroughly researched answer in an upcoming issue of Outdoor Humans. If I don’t know the answer, I’ll reach out to biologists, outdoor enthusiasts, and other experts to get you a solid explanation.

Shameless plugs for my work around the web

Because there’s never enough cemetery content during the month of October, I’m sharing one of my all-time favorite pieces. In 1897, a grieving young widow in Southwest Missouri couldn’t stand the idea of never again seeing her dearly departed’s face. What’s a gal to do but build a specialty tomb that allowed her to gaze upon him whenever she pleased? Imagine the pandemonium when the entire town of Nevada found out about it.

That’s it for this month’s edition of Outdoor Humans. We’ll chat again in November. This month, I’ll be keeping in mind folks affected by Hurricane Helene and the impacts of climate change, and hope you too will find ways to support them.

Thanks for reading. See you out there!

Nicole Garner Meeker